By: Alicia J. Kowaltowski, M.D., Ph.D., Universidade de São Paulo

Obesity enhances the incidence and prevalence of many diseases, but is still increasing worldwide. Our group is focused on understanding mechanisms involved in the protective effects of maintaining a normal body weight, in order to uncover new targets for obesity-related diseases. We do this by studying rodents that eat ad libitum (as much as they want) and develop obesity versus animals on a calorically-restricted diet. Calorically-restricted rodents have been shown to have less oxidative damage and age-related diseases, as well as extended lifespans.

Many of the effects of caloric restriction, predictably, involve changes in energy metabolism and mitochondria, the central hub of energy metabolism. Recently, while investigating mechanisms in which calorie restriction prevents excitotoxic neuronal death (Amigo et al., 2017), we found that mitochondria from calorically-restricted animals can take up Ca2+ ions faster and in larger quantities. The higher buffering capacity these mitochondria have promotes protection against neuronal death caused by excessive Ca2+ in the cytosol.

Because this is a completely new effect of caloric restriction, we decided to investigate if mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake was also modified in the liver (Menezes-Filho et al., 2017). We found that liver mitochondria from calorie restricted mice could also take up more Ca2+, and that this was related to protection against ischemic damage. Overall, the finding that caloric intake affects mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is interesting because Ca2+ is a well-known modulator of energy metabolism and mitochondrial oxidant production. Based on these initial findings, we hope to uncover more connections between metabolic regulation, redox state, caloric intake and Ca2+ in futures studies.

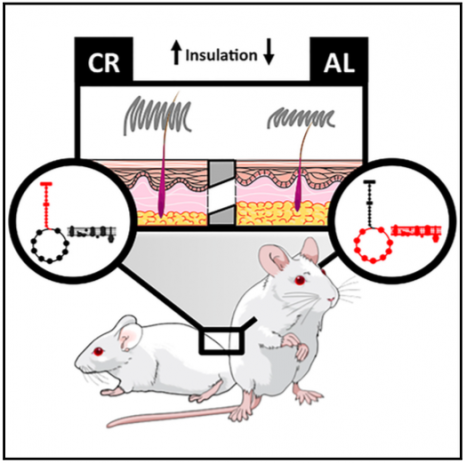

While studying calorically-restricted mice, we noticed that they had different fur from obese ad libitum fed animals. We then decided to investigate changes in the skin and fur of calorie restricted animals, and found many modifications, both in the structure and metabolism of the skin. One interesting finding was that the fur in calorically-restricted mice has a higher insulation capacity, and is necessary for them to thrive: shaving calorie restricted animals makes them lose muscle mass. We are not sure how these results relate to humans, who aren´t very furry, but believe this is an evolutionary adaptation to deal with heat loss. Although the skin is our largest organ, it is not often studied, and there are almost no related findings. We hope that with this study and the development of methodology to monitor metabolism in the skin, more interest will arise.

Amigo I, Menezes-Filho SL, Luévano-Martínez LA, Chausse B, Kowaltowski AJ. Caloric restriction increases brain mitochondrial calcium retention capacity and protects against excitotoxicity. Aging Cell. 2017 16:73-81.

Forni MF, Peloggia J, Braga TT, Chinchilla JEO, Shinohara J, Navas CA, Camara NOS, Kowaltowski AJ. Caloric restriction promotes structural and metabolic changes in the skin. Cell Rep. 2017 20:2678-2692.

Menezes-Filho SL, Amigo I, Prado FM, Ferreira NC, Koike MK, Pinto IFD, Miyamoto S, Montero EFS, Medeiros MHG, Kowaltowski AJ. Caloric restriction protects livers from ischemia/reperfusion damage by preventing Ca2+-induced mitochondrial permeability transition. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017 110:219-227.

— Published

Category: Redox Biology

By: Sam Giordano on behalf of the Trainee Council

Finding a good mentor is challenging…

Being a good mentor is just as challenging, but 2016 SfRBM Mentoring Excellence Award Winner, Dr. Rakesh Patel, a Professor in Pathology from the University of Alabama at Birmingham fits the bill. In fact, Dr. Patel excels at mentoring, but I may be a bit biased having been lucky enough to be his mentee during my graduate training.

We all learn from our mentors, and Dr. Patel said the best advice he received as a mentee was to “always persevere, even when experiments don’t work.” He continued, “always ask questions, be critical of your own work, as well as others and most of all enjoy what you do.”

Dr. Patel hopes that as he mentors his trainees, he continues teaching his mentees these important lessons. He also recommends that when trainees are looking for a mentor, look at your potential mentor’s mentoring track and their mentor’s mentoring track record; it can give great insight into the type of mentor they are and how they support their trainees.

In receiving the 2016 SfRBM Mentoring Excellence Award, Dr. Patel received numerous nomination letters from trainees (and even faculty) from different countries with diverse experiences and backgrounds. When I asked how he mentors such a diverse group of people his advice fit perfectly into the current trends in medicine and science. “To borrow a current buzz term, I always try to ‘personalize’ mentoring. I use the analogy that whatever parenting approach was successful for my older child, rarely works for my youngest, and vice versa.”

Dr. Patel also reminds us that a good mentor considers professional and personal goals of their mentees and takes the time to understand what motivates them. This can help the mentees harness his or her strengths and overcome their weaknesses. He also points out that as the trainees grow and learn, the mentor-mentee relationship will evolve, hopefully in a mutually beneficial way. In a healthy mentor-mentee relationship, honest and open communication is key, and it is the best way to have a successful and long lasting healthy mentoring relationship.

— Published

By Luciana Hannibal, Ph.D.

Team success goes hand in hand with the professional development of its members. New employees are selected according to background education (know-how theory), previous accomplishments (know-how experience) and potential (know-how to grow). These important metrics help to recruit candidates who are best suited for the position, and capture them at a stage of high self-motivation and drive. Only a few however, will stand out for their achievements, even when the same selection process has been applied to all. Why? A pool of employees will choose to remain in a professional comfort-zone, meeting personal and team demands satisfactorily. Others will strive to further their professional development and to make a difference in the team. Some will go beyond and prepare themselves to lead their own teams in the future. Even after careful recruitment, a population of talented individuals may however derail from successful career development. A mismatch of talents and projects can hamper advancement regardless of individual mindset. Researchers in leading positions are expected to excel at understanding the scientific problem, providing new ideas and solutions, teaching and supervising, cooperating effectively with internal and external colleagues and recruiting copious amounts of extramural funding. Optimizing self-reliance of the team is thus crucial for individual and collective return on investment, and this involves aligning talents with projects. Team leaders must identify individual strengths to effectively assign project roles, and employees must be visible for their most valuable talents. Self-motivated employees, as they typically land in the new job, constitute an invaluable asset.

Here is a brief guide on how to blend projects with selected talent types:

— Published

Categories: Education, Redox Biology, Free Radical Biology and Medicine

Guest Blog By: Peter Vitiello, PhD - Assistant Scientist, Environmental Influences on Health and Disease Group, Sanford Research

Science advocates across 65 countries will participate in over 600 coordinated marches to highlight the influence of research on our society and promote a call of support for the research community. Some skeptics think these organized events can paint scientists as a partisan special interest group in polarized political climates. Regardless of your opinion on the value of these marches, it is undeniable that many scientists have a renewed desire to voice their opinion by building long-standing relationships with their local communities and representatives in government.

There are several easy ways to communicate with your local representatives. Social media outlets such as Twitter can quickly engage groups of individuals and comments are monitored by staffers. However, the impact of social media activism can depend on your number of followers. Although email may be a preferred method, writing a letter to your representative’s local office is often more effective because it guarantees that it will be read. The most effective thing to do is call their local office because it is the most timely approach and staffers will document and communicate your message. Just be sure to be kind and thank the staffers answering the phones since they may be fielding nonstop phone calls for eight hours every day.

While this strategy is an excellent way to register your message, it doesn’t necessarily communicate the value of your opinion as a scientist. An excellent way to articulate information about yourself and your professional opinion is to communicate with people in your community, since most of them have never met a single scientist. I was recently able to interact with several community organizations to discuss the influence of research on our society. One group was from the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute which provides learning opportunities for people over 50 years old. Another group was the Lions Club comprised of local business leaders. These networking organizations (local chambers, policy advocacy groups) can also serve as a gateway to local representatives. I found these dynamic forums to be an excellent way to overcome and important stigmatic barrier, allowing community members to interact with local scientists.

As researchers, we are constantly inundated with communicating our ideas and findings to the rest of the scientific community but often neglect ways to interact with people and leaders in our own backyards. The best way to be heard is to take ownership of being a community leader, a responsibility that should be embraced by every scientist.

— Published

Dr. Yvonne Janssen-Heininger of the University of Vermont’s Dept. of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine grew up in the Netherlands and first discovered her love of lung research as an undergraduate, when she looked at different organ tissues under a microscope. Yvonne and her team currently investigate the role of redox biology and fibrosis in the lungs to elucidate pathology mechanisms and to develop novel drugs to treat chronic lung disease.

Dr. Janssen-Heininger is a leading author in scientific publications and her discoveries are highly cited by her peers (Hirsch index h = 46, Scopus). She is a world-leading expert on protein-thiol redox signaling, the biology of epithelial cells and pulmonary fibrosis. Since 2010, Yvonne has served as a member and elected Chair of the Lung Injury Repair and Remodeling Study Section of the National Institutes of Health. She has been a member of SfRBM since 1997 and served on the leadership Council as Secretary-Treasurer.

Although Yvonne loves science and enjoys reading articles on lung injury, she also enjoys reading Nicholas Sparks novels; it’s on her recommended reading list! Yvonne also enjoys cooking and calls herself a “hit and mostly miss cook” because she is forever trying new recipes, which range from absolutely delicious to maybe not so great.

SfRBM’s Women in Science Committee is proud to recognize Yvonne Janssen-Heininger and her research. To learn more about Yvonne and other amazing female scientists like Daret St. Clair and Samantha Giordano, check out the SfRBM “Featured Women in Science” page here (http://sfrbm.org/resources/women-in-science/).

— Published

Category: SfRBM Member Profile